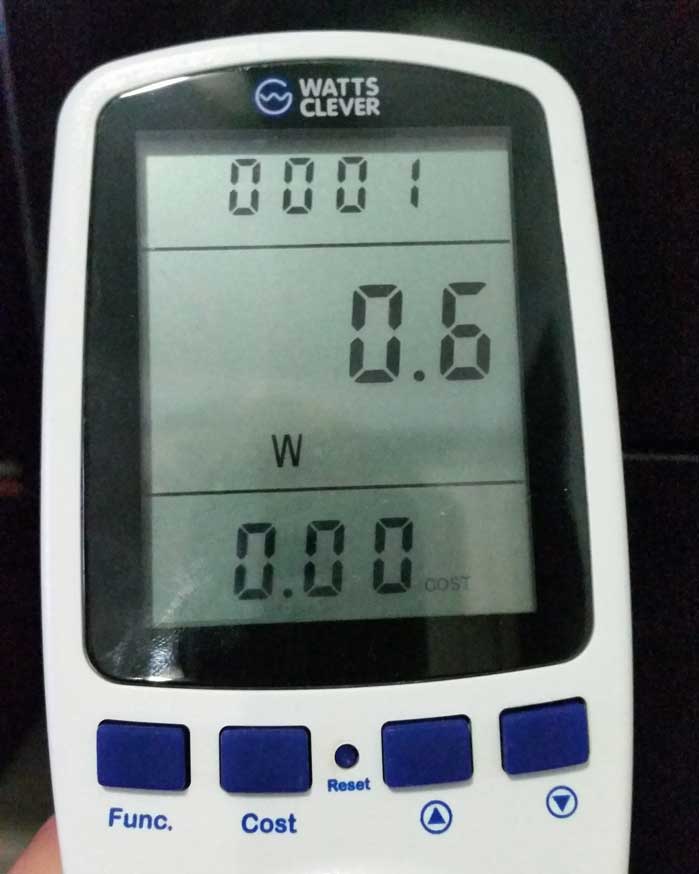

I’m pretty impressed by the Intel NUC’s (D34010WYB) power consumption. When the NUC is powered off the power button LED is illuminated with a very weak green. You can only really see the green with the lights off in a dark the room. In this standby state the NUC consumes 0.6 Watts of power. It’s a modest amount that could probably come down by playing around with the WOL settings in the BIOS.

Pic1. NUC in stand-by

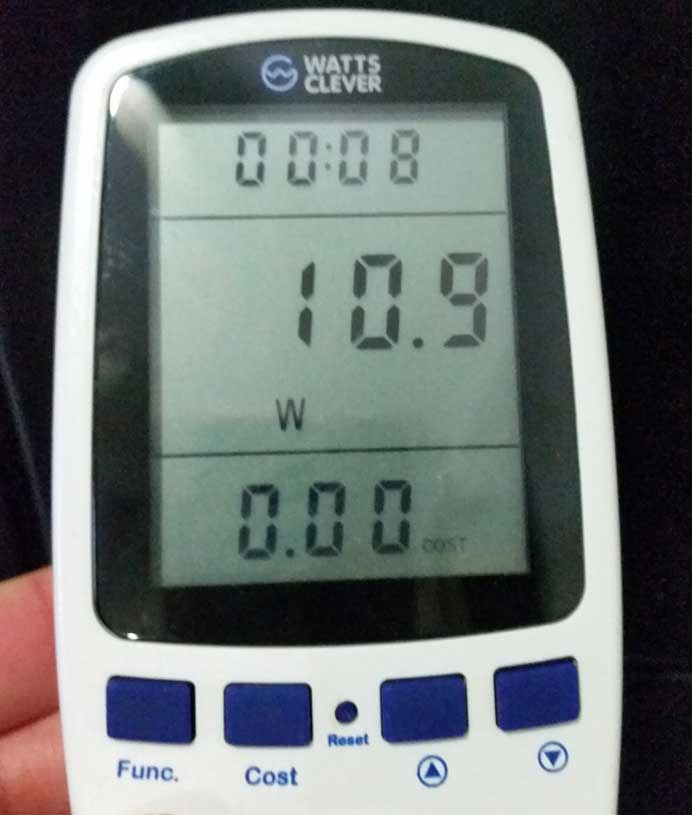

During boot-up of ESXi from USB the NUC consumed between 14-15 Watts. Once ESXi booted with no VMs running the NUC consumes a steady 10.9 watts. I have to be honest and say I’m pretty blown away by that. That’s soo much better than I imagined!

Pic2. NUC at idle booted into ESXi

The Test

The 4th Generation NUCs run the Haswell microarchitecture. A key feature of this architecture is their low power consumption. So I was curious to see how much power it would draw under a CPU stress test.

My test was by no means scientific. I ran two VMs with ESXi.

VM1 -- VMware Virtual Center Appliance with 8 GB memory

VM2 -- Windows Server 2012 R2 with 2 GB memory and 4 CPUs

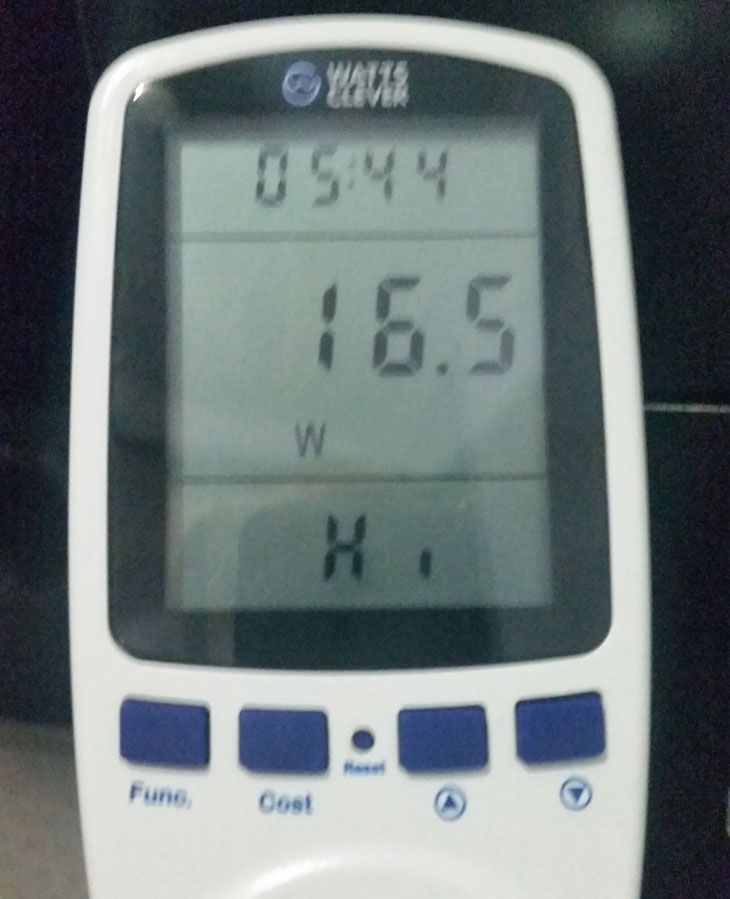

On VM2 I ran a CPU stress test tool called Prime95. A freeware application that finds Mersenne prime numbers and has become a popular stress testing tool in the overclocking community. The CPU on VM2 instantly jumped to 100%. Back over on the ESXi Host the physical CPU also jumped up to it’s maximum 1.7 Ghz. Looking over at the power meter during this time showed a maximum of 16.5 watts.

Pic3. NUC under load

The Cost

So at idle the NUC comsumes a steady 10.9 watts an hour. If I factor that out over the year by the typical cost of electricity in Australia.

10.9 watts x 24 hrs x 365 = 95.484 Kw/h x .26 (AUD) = $24.82 AUD/year

The Verdict

The low power consumption of the NUC was only a small selling point of purchasing it. It’s nice to now know that it will come with some really savings over time. I’ll now be gladly retiring the old Lenovo desktops in favour of a few NUCs.

Articles in this series

Part 1: The NUC Arrival

Part 2: ESXi Owning The NUC

Part 3: Powering a NUC Off A Hampster Wheel

Part 4: The NUC for Weight Weenies

Part 5: Yes, you can have 32GB in your NUC

Hello.

I have a NUC5i5RYK, running ESXi 6.0. My CPU on ESXi and my Ubuntu servers running on it, reports roughly 1600 mhz, which is fine. But when I stress one of the virtual machines, I’d figure ESX should crank up the Mhz to 2.7 with the speedstep technology.

Do you know if it happens, even though cat /proc/cpuinfo shows otherwise?

Kind regards Jacob 🙂

Hi Jacob,

I thought about discussing the Turbo Boost features of the CPU in the post but there was just too much going on behind the scenes on the CPU. Might be a topic in the future…

2.7Ghz is the theoretical maximum the CPU will do only on one core. There are a lot of factors that also depends on it hitting that number. Current and Power consumption, number of active cores and workloads on those cores at the given time. As soon as the CPU gets a little hot it will back off and there’s not much ESXi or you can do about it. I guess you can mess with voltage and power settings in the BIOS but I don’t want to get into that kind of stuff.

What you’re seeing in /proc/cpuinfo is just what ESXi is letting you see. And what ESXi is seeing is just what the CPU is letting it see. It will never show the Max Turbo Frequency but rather the Base Frequency. These values aren’t dynamic, so they won’t change.

If you run your VM at 100%, one way I have found to see if Turbo Boost is stepping up is to go to the ESXi CLI and run ESXTOP. If the CPU %USED is above 100% it’s a good sign the clock speed is being increased.

…but in a nutshell, Yes, ESXi will allow what extra Mhz it can from the CPU to the VM when available.

Thanks,

Mark

Hello Mark!

Thank you very much for the clarification 🙂

Kind regards.

Jacob